Physical Therapist's Guide to Below-Knee Amputation

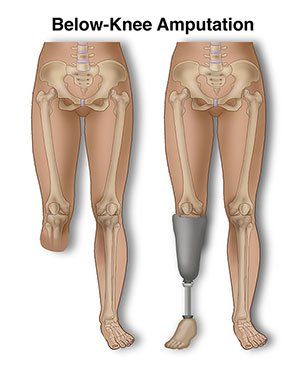

Lower-limb amputation is a surgical procedure performed to remove a limb that has been damaged due to trauma or disease. Below-knee or "trans-tibial" amputation comprises 23% of lower-limb amputations. Amputation is possible in any age group, but the prevalence is highest among people aged 65 years and older.

What is a Below-Knee Amputation?

Below-knee amputation (BKA) is a surgical procedure performed to remove the lower limb below the knee when that limb has been severely damaged or is diseased. Most BKAs (60%–70%) are performed due to peripheral vascular disease, or disease of the circulation in the lower limb. Poor circulation limits healing and immune responses to injury, and foot or leg ulcers may form and not heal. They may develop an infection, and it could spread to the bone becoming severe enough to be life-threatening. Amputation is performed to remove the diseased tissue and prevent the further spread of infection.

If BKA surgery is necessary, it is usually performed by a vascular or orthopedic surgeon. The diseased or severely injured part of the limb will be removed, keeping as much of the healthy tissue and bone as possible. The surgeon shapes the remaining limb to allow the best use of a prosthetic leg after recovery.

The need for BKA is caused by conditions including:

- Peripheral vascular disease

- Diabetes

- Infection

- Foot ulcer

- Trauma, causing the lower leg to be crushed or severed

- Tumor/cancer (see link references at the bottom of the page for more information)

How Can a Physical Therapist Help?

Prior to BKA surgery

Before your surgery, your physical therapist may:

- Prescribe exercises for preoperative conditioning, and to improve the strength and flexibility of the hip and knee

- Teach you how to walk with a walker or crutches

- Educate you about what to expect after the procedure

Immediately after surgery

Your hospital stay will be approximately 5 to 14 days. Your wound will be bandaged, and you may also have a drain at the surgery site, a tube that is inserted into the area to help remove excess fluid. Pain will be managed with medication.

Physical therapy will begin soon after surgery when your condition is stable and the doctor clears you. A physical therapist will review your medical and surgical history, and visit you at your bedside. Your first 2 to 3 days of treatment may include:

- Gentle stretching and range-of-motion exercises

- Learning to roll in bed, sit on the side of the bed, and move safely to a chair

- Learning how to position your surgical limb to prevent contractures (the inability to straighten the knee joint fully, which results from keeping the limb bent too much)

When you are medically stable, the physical therapist will help you learn to move about in a wheelchair, and stand and walk with an assistive device.

Prevention of contractures

A contracture is the development of soft-tissue tightness that limits joint motion. The condition occurs when muscles and soft tissues become stiff and fibrous from lack of movement. The most common contracture following BKA occurs at the knee when it becomes flexed and unable to straighten. The hip may also become stiff. It is important to prevent contractures early.

Contractures can become permanent if not addressed following surgery, throughout recovery, and after rehabilitation is completed. Contractures can make it difficult to wear your prosthesis, and make walking more difficult, increasing the need for an assistive device like a walker.

Your physical therapist will help you maintain normal posture and range of motion at your knee and hip. The therapist will teach you how to position your limb to avoid development of a contracture, and show you stretching and positioning exercises to maintain normal range of motion.

Swelling and compression

It is normal to experience post-operative swelling. Your therapist will help you maintain compression on your residual limb to protect it, reduce and control swelling, and help it heal. Compression can be accomplished by:

- Wrapping the limb with elastic bandages

- Wearing an elastic shrinker sock

These methods also help shape the limb to prepare it for fitting the prosthetic leg.

In some cases a rigid dressing, or plaster cast, may be used instead of elastic bandages. An immediate post-operative prosthesis made with plaster or plastic may also be applied. The method chosen depends on each person’s situation. Your physical therapist will help monitor the fit of these devices and instruct you in their use.

Pain management

Your physical therapist will help with pain management in a variety of ways, including:

- Electrical stimulation and TENS (transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation) for pain modification. (Gentle electrical stimulation of the skin to relieve pain by blocking nerve signals from underlying pain receptors.)

- Manual therapy, including massage and joint manipulation to improve circulation and joint motion.

- Stump management, including skin care and stump sock use.

- Desensitization to help modify how sensitive an area is to clothing pressure or touch. Desensitization involves stroking the skin with different types of touch to help reduce or eliminate the sensitivity reaction to the stimulus.

See the guide on Phantom Pain for more details on pain after amputation .

Your physical therapist will work with a prosthetist to prescribe the best prosthesis for your life situation and activity goals. You will receive a temporary prosthesis at first while your residual limb continues to heal and shrink/shape over the first 6 to 9 months of healing. The prosthesis will be modified to fit as needed over this time.

After you move from acute care to rehabilitation, you will learn to function more independently. Your physical therapist will help you master wheelchair mobility and walking with an assistive device like crutches or a walker. Your therapist will also teach you the skills you need for successful use of your new prosthetic limb. You will learn how to care for your residual limb with skin checks and hygiene, and continue contracture prevention with exercise and positioning.

Your physical therapist will teach you how to put your new prosthesis on and take it off, and how to manage a good fit with the socket type you receive. The therapist will help you to gradually build up tolerance for wearing your prosthesis for increasingly longer times, while protecting the skin integrity of your residual limb. You will continue to use a wheelchair for getting around, even after you get your permanent prosthesis, for times when you are not wearing the limb.

Prosthetic training is a process that can last up to a full year. You will begin when the physician clears you for weight bearing on the prosthesis. Your physical therapist will help you learn to stand, balance, and walk with the prosthetic limb. Most likely you will begin walking in parallel bars, then progress to a walker, and later as you get stronger, you may progress to using a cane before walking independently without any assistance. You will also need to continue strengthening and stretching exercises to achieve your fullest potential as you return to many of the activities you performed before your amputation.

Can this Injury or Condition be Prevented?

It is believed that 60% of amputations are preventable. The leading cause of BKA is complications from diabetes, such as peripheral vascular disease, open wounds, and infection. Prevention and management of diabetes and lower-extremity circulation problems can greatly reduce the risk of developing conditions that lead to the need for lower-extremity amputation. Make sure you protect your feet by wearing adequate foot wear. It is also important to examine your lower extremities and feet daily for signs of skin problems, such as redness or discoloration, swelling, blisters, scratches, or open wounds. It is important to promptly consult your primary health care provider should you notice a problem. Prevention of infection is a primary way to prevent below-knee amputation.

It is also important to stop smoking. Smoking cigarettes can interfere with healing, and it is associated with reamputation risk 25 times greater than nonsmokers.

Real Life Experiences

Ed is a 75-year-old gentleman who has diabetes and peripheral artery disease of the right lower leg. Due to the lack of circulation in his lower leg, Ed has developed an open wound that has become infected. Despite the best efforts of medical care, the infection has continued to spread. Because the infection is now threatening Ed’s health and well-being, the decision is made to amputate the diseased part of his lower leg. Ed is referred to physical therapy for preoperative exercise instruction, and to learn how to walk with a walker before his scheduled surgery.

The day after Ed’s surgery, a hospital physical therapist comes to Ed's room to begin treatment. She teaches him to perform some gentle exercises for the affected limb, and exercise his uninvolved leg and arms. She helps him safely roll in bed, and teaches him about keeping his knee straight on the amputated side, and how to support his leg to reduce swelling.

As Ed's residual limb heals, his physical therapist helps him get out of bed and sit in a chair. He learns to stand on 1 leg with a walker next to his bed. As he gets stronger, he advances to 1-leg walking with a walker, with close assistance from the physical therapist.

When Ed is medically stable, he transfers to a rehabilitation facility. There, he works closely with the rehabilitation physical therapist to learn how to care for the skin on his residual limb, how to position and stretch his leg to prevent contractures, and how to wrap the stump and use shrinker socks to reduce swelling and shape his residual limb. Soon, he is able to get around by propelling his wheelchair. He also works hard doing strengthening and stretching exercises as directed by his physical therapist. He gains strength and balance, allowing him to walk farther without becoming tired.

Ed receives a temporary, or preparatory, prosthesis. The prosthetist fabricated a socket from a cast of his residual limb. It was connected to a pylon and prosthetic foot. Ed is now ready to begin his gait training in physical therapy with full weight bearing on his amputated leg. Ed and his physical therapist will monitor the fit of the socket several times a day to avoid pressure points on his residual limb.

Ed is now able to function with minimal assistance and is discharged home. His family has been trained to help keep him safe and assist him. Ed continues physical therapy as an outpatient, and continues to build his strength and improve his walking ability. He is guided in the use of his temporary prosthesis as his stump continues to reshape. Adjustments to the prosthesis will be made as he continues rehabilitation and progresses over the next 1 to 2 months, prior to receiving his permanent prosthesis.

When Ed’s residual limb stops shrinking, about 8 months after his surgery, he receives his permanent prosthesis. He works with his physical therapist and prosthetist to ensure a good fit, and to learn to improve his walking pattern. After much hard work, Ed is discharged from physical therapy, having achieved his goal of walking independently without an assistive device.