Physical Therapist's Guide to Rotator Cuff Tear

The "rotator cuff" is the group of 4 muscles and their tendons responsible for keeping the shoulder joint stable. Injuries to the rotator cuff are common—either from accident or trauma, or with repeated overuse of the shoulder. Risk of injury can vary, but generally increases as a person ages. Rotator cuff tears are more common later in life, but also can occur in younger people. Athletes and heavy laborers are often affected; older adults can injure the rotator cuff when they fall on or strain the shoulder. When left untreated, a rotator cuff tear can cause severe pain and a decrease in the ability to use the arm. Physical therapists help people with rotator cuff tears address pain and stiffness, restore movement to the shoulder and arm, and improve their activities of daily living.

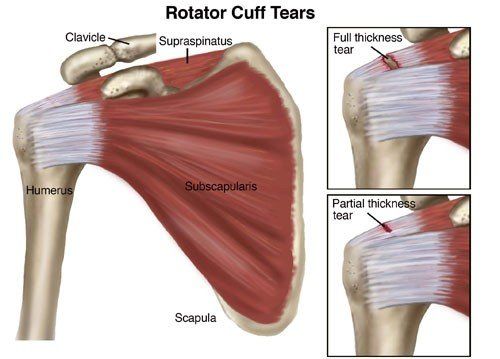

What is a Rotator Cuff Tear?

The "rotator cuff" is a group of 4 muscles and their tendons (tissues that attach muscles to bones), which connects the upper arm bone, or humerus, to the shoulder blade. The important job of the rotator cuff is to keep the shoulder joint stable. Sometimes, the rotator cuff becomes inflamed or irritated due to heavy lifting, repetitive arm movements, or trauma such as a fall. A rotator cuff tear occurs when injuries to the muscles or tendons cause tissue damage or disruption.

Rotator cuff tears are called either "full thickness" or partial thickness," depending on how severe they are.

- Full-thickness tears extend from the top to the bottom of a rotator cuff muscle/tendon.

- Partial-thickness tears affect at least some portion of a rotator cuff muscle/tendon, but do not extend all the way through.

Tears often develop as a result of either a traumatic event or long-term overuse of the shoulder. These conditions are commonly called “acute” or “chronic.”

- Acute rotator cuff tears are those that occur suddenly, often due to traumas, such as a fall or lifting of a heavy object.

- Chronic rotator cuff tears are much slower to develop. These tears are often the result of repeated actions with the arms working above shoulder level, such as with ball-throwing sports or certain work activities.

People with chronic rotator cuff injuries often have a history of rotator cuff tendon irritation that causes shoulder pain with movement. This condition is known as shoulder impingement syndrome.

Rotator cuff tears also may occur in combination with injuries or irritation of the biceps tendon at the shoulder, or with labral tears (to the ring of cartilage at the shoulder joint). Your physical therapist will explain the particular details of your rotator cuff tear.

| Rotator Cuff Tear: See More Detail |

How Does it Feel?

People with rotator cuff tears can experience:

- Pain over the top of the shoulder or down the outside of the arm

- Shoulder weakness

- Loss of shoulder motion

- A feeling of weakness or heaviness in the arm

- Inability to lift the arm to reach up, or reach behind the back

- Inability to perform common daily activities due to pain and limited motion

How Is It Diagnosed?

To help pinpoint the cause of your shoulder pain, your physical therapist will complete a thorough examination that will include learning details of your symptoms, assessing your ability to move your arm, identifying weakness, and performing special tests that may indicate a rotator cuff tear. For instance, your physical therapist may raise your arm, move your arm out to the side, or raise your arm and ask you to resist a force, all at specific angles of elevation.

In some cases, the results of these tests might indicate the need for a referral to an orthopedist or other professional for imaging tests, such as ultrasound imaging, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or a computed tomography (CT) scan.

How Can a Physical Therapist Help?

Once a rotator cuff tear has been diagnosed, you will work with your orthopedist and physical therapist to decide if you should have surgery or if you can try to manage your recovery without surgery.

If you don't need surgery, your physical therapist will work with you to restore your range of motion, muscle strength, and coordination, so that you can return to your regular activities. In some cases, you may learn to modify your physical activity so that you put less stress on your shoulder.

If you decide to have surgery, your physical therapist can help you both before and after the procedure.

Regardless of which treatment you have—physical therapy only, or surgery and physical therapy—early treatment can help you speed the healing process and avoid permanent damage.

If You Have an Acute Injury

If a rotator cuff tear is suspected following a trauma, seek the attention of a physical therapist or other health care provider to rule out the possibility of serious life- or limb-threatening conditions. Once serious injury is ruled out, your physical therapist will help you manage your pain and will prepare you for the best course of treatment.

If You Have a Chronic Injury

A physical therapist can help manage the symptoms of chronic rotator cuff tears as well as improve how your shoulder works. For large rotator cuff tears that can't be fully repaired, physical therapists can teach special strategies to improve shoulder movement. However, if physical therapy and conservative treatment alone do not improve your function, surgical options may exist.

If You Have Surgery

If your condition is severe, you may require surgery to restore use of the shoulder; physical therapy will be an important part of your recovery process. The repaired rotator cuff is vulnerable to reinjury following shoulder surgery; working with a physical therapist is crucial to safely regaining full use of the injured arm. After the surgical repair, you will need to wear a sling to keep your shoulder and arm protected as the repair heals. Your physical therapist will apply treatments during this phase of your recovery to reduce pain and gently begin to restore movement. Once you are able to remove the sling for exercise, your physical therapist will begin your full rehabilitation program.

Your physical therapist will design a treatment program based on both the findings of the evaluation and your personal goals. Your physical therapist will guide you through your postsurgical rehabilitation, which will progress from gentle range-of-motion and strengthening exercises to activity- or sport-specific exercises.

Your treatment program most likely will include a combination of exercises to strengthen the rotator cuff and other muscles that support the shoulder joint. The time line for your recovery will vary depending on the surgical procedure and your general state of health, but return to sports, heavy lifting, and other strenuous activities might not begin until 4 months after surgery and full return may not occur until 9 months to 1 year after surgery. Following surgery, y our shoulder will be susceptible to reinjury. It is extremely important to follow the postoperative instructions provided by your surgeon and physical therapist.

Your rehabilitation will typically be divided into 4 phases:

- Phase I (maximal protection). Phase 1 of treatment lasts for the first few weeks after your surgery, when your shoulder is at the greatest risk of reinjury. During this phase, your arm will be in a sling. You will likely need assistance or need strategies to accomplish everyday tasks, such as bathing and dressing. Your physical therapist will teach you gentle range-of-motion and isometric strengthening exercises, provide hands-on treatments (manual therapy), such as gentle massage, offer advice on reducing your pain, and may use techniques such as cold compression and electrical stimulation to relieve pain.

- Phase II (moderate protection). This next phase has the goal of restoring mobility to the shoulder. You will reduce the use of your sling, and your range-of-motion and strengthening exercises will become more challenging. Exercises will be added to strengthen the "core" muscles of your trunk and shoulder blade (scapula), and the rotator-cuff muscles that provide additional support and stability to your shoulder. You will be able to begin using your arm for daily activities, but will still avoid heavy lifting. Your physical therapist may use special hands-on mobilization techniques during this phase to help restore your shoulder's range of motion.

- Phase III (return to activity). This phase has the goal of restoring your strength and joint awareness to equal that of your other shoulder. At this point, you should have full use of your arm for daily activities, but you will still be unable to participate in activities such as sports, yard work, or physically strenuous work-related tasks. Your physical therapist will advance the difficulty of your exercises by adding weight or by having you use more challenging movement patterns. A modified weight-lifting/gym-based program may also be started during this phase.

- Phase IV (return to occupation/sport). This phase will help you return to work, sports, and other higher-level activities. During this phase, your physical therapist will instruct you in activity-specific exercises to meet your needs. For certain athletes, this may include throwing and catching drills. For others, it may include practice in lifting heavier items onto shelves, or instruction in proper positioning for everyday tasks such as raking, shoveling, or doing housework.

Can this Injury or Condition be Prevented?

A physical therapist can help you reduce the worsening of the symptoms of a rotator cuff tear and may decrease your risk of worsening a tear, especially if you seek assistance at the first sign of shoulder pain or discomfort. To avoid developing a rotator cuff tear from an existing shoulder problem, it is imperative to stop performing actions that could make it worse. Your physical therapist can help you strengthen your rota t or cuff muscles, train you to avoid potentially harmful positions, and determine when it is appropriate for you to return to your normal activities.

To maintain shoulder health and prevent rotator cuff tears, physical therapists recommend that you:

- Avoid repeated overhead arm positions that may cause shoulder pain. If your job requires such movements, seek out the advice of a physical therapist to learn arm positions that may be used with less risk.

- Apply rotator-cuff muscle and shoulder-blade strengthening exercises into your normal exercise routine. The strength of the rotator cuff is just as important as the strength of any other muscle group. To avoid potential harm to the rotator cuff, general strengthening and fitness programs may improve shoulder health.

- Practice good posture. A forward position of the head and shoulders has been shown to alter shoulder-blade position and create shoulder impingement syndrome.

- Avoid sleeping on your side with your arm stretched overhead, or lying on your shoulder. These positions can begin the process that causes rotator cuff damage and may be associated with increasing your pain level.

- Avoid smoking; it can decrease the blood flow to your rotator cuff.

- Consult a physical therapist at the first sign of symptoms.

MoveForwardPT.com, the official consumer Website of the American Physical Therapy Association,© 2017